The findings of a study by neurotechnology company Dreem are a “game-changer” in sleep monitoring, according to its scientific director.

The French start-up’s Octave IRBA study concluded that its Dreem 2 AI-enabled headband for improving sleep problems and at-home diagnosis, is on par with medical professionals in identifying stages of sleep.

Dreem’s headband uses sensors and a deep learning algorithm to measure brain activity, heart rate, and movement and breathing.

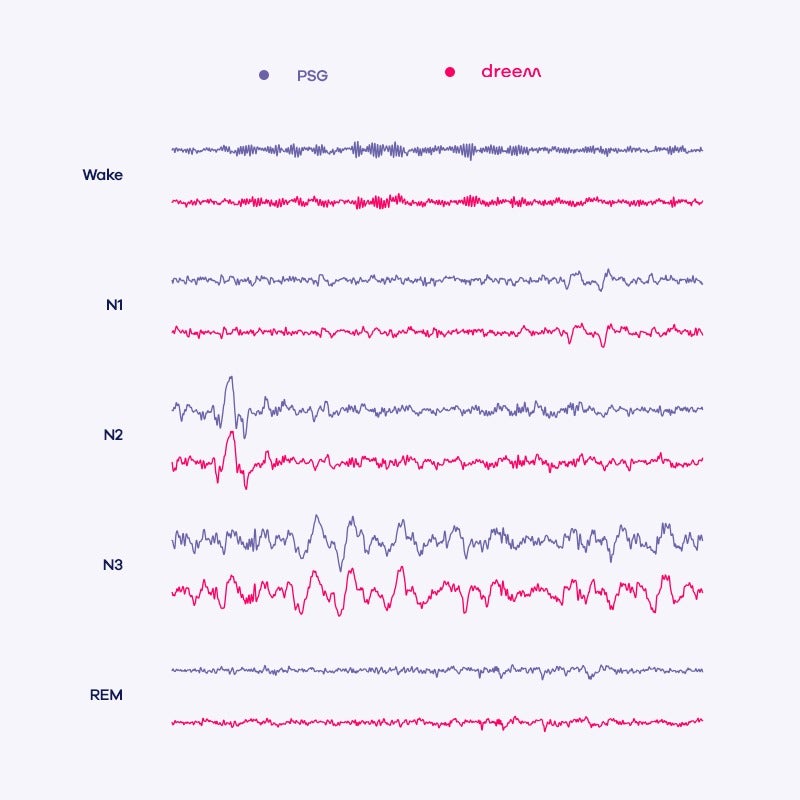

These results were compared with those from polysomnography (PSG) — the “gold standard” sleep test for diagnosing disorders — which showed them to be broadly the same.

Dreem scientific director Pierrick Arnal said: “We see Octave IRBA as the first step moving towards a complete solution for diagnosing sleep disorders.

“I think it’s really important for the sleep community — when I talk with physicians they say they’ve been waiting for years, even decades for a tool that tracks brain activity at home — but no other companies had been able to do this until now.

“It’s a real game-changer because it is so important as a researcher to see the proper validation of the work you are doing.”

How does Dreem’s AI-enabled headband diagnose and treat sleeping problems?

The Dreem 2 headband has five electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors that measure brain activity, a pulse oximeter to monitor heart rate and an accelerometer to record movement and breathing during the night.

This data is used by the headband in two ways — firstly, it acts on the readings it picks up in real-time, using audio features to improve quality of sleep.

Options include using bone conduction technology to transmit bursts of pink noise — a frequency of sound that enhances deeper periods of sleep — from the forehead straight to the inner ear.

Information from the sensors is also used to wake the user during a period of lighter sleep, within a selected time frame, so as not to disrupt the natural rhythm of sleep.

Secondly, when the headband is combined with the Dreem smartphone app, these results are used to provide daily reports on the user’s sleeping habits, for example how long it took them to get to sleep and how many times they woke during the night.

The app, which can be downloaded for free on iOS and Android devices, provides insights on how to improve sleep quality by helping the user understand sleeping patterns, and recommending a suitable sleep program or schedule.

Arnal said: “If it sees an irregular sleeping pattern over a number of nights, the app can recommend you should see a doctor — just something as simple as that could be really important.”

The Octave IRBA study: How it was carried out and what it found

The Octave IRBA study was conducted earlier this year, and involved using Dreem’s AI headband to monitor one night’s sleep in 25 healthy people with mild cases of insomnia or depression.

These participants wore the Dreem headband and a polysomnography device while sleeping, and were also monitored by five sleep experts.

The results were published in June 2019 on the online biology archive bioRxiv, and showed the headband is able to produce readings with a “strong correlation” to polysomnography when measuring brain activity, heart rate and breathing.

Dreem says this demonstrated the headband is an affordable, comfortable, and user-friendly, but still highly accurate alternative to polysomnography — the original intention of the study.

Polysomnography was also used to plot the various stages within the sleep cycle, which range from lighter stages such as wakefulness to deeper phases of rapid eye movement (REM) — the results of this were then verified by five sleep experts.

Dreem’s headband is able to use the readings it picks up to detect these sleep stages automatically, and the Octave IRBA study found this could be done with broadly similar levels of accuracy compared with the sleep experts.

Arnal believes these conclusions are the reason the sleep community is “really interested” in the data from the study.

What else does the future hold for Dreem?

The study claimed the headband “paves the way for high-quality, large-scale, longitudinal sleep studies”, meaning future research can be carried out using data from more than one night to detect more serious problems.

Arnal said: “That’s the whole point of Dreem — making this device available for everyone for longitudinal assessment [repeated studies over time to gain a greater sample size and more thorough data].

“It is easier to get good results from patients without a lot of conditions, but the next step would be to do it with patients with different and more serious sleep disorders, like sleep apnoea, narcolepsy or severe insomnia.

“If we look at how sleep disorders are diagnosed right now, the system is not working at all — 85% of patients with sleep apnoea are undiagnosed. A lot of people are just living with the condition and that can lead to more serious problems like cardiovascular diseases.”

Dreem is also hoping to make the AI headband available on prescription in the future — right now it can only be recommended by a doctor and purchased online for €399 ($445).

Arnal said the company is working with clinics and doctors to make them more aware of the device.

He added that Dreem is also attempting to secure a CE marking by 2020, which would make the headband an approved medical device in Europe.