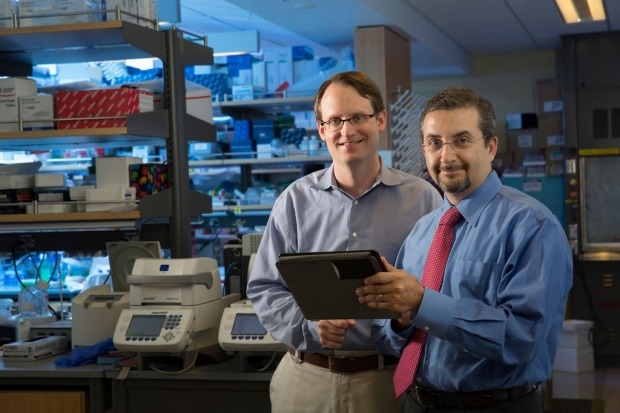

Researchers Maximilian Diehn and Ash Alizadeh, along with their teams have designed the new technology inspired by a sports playbook.

The new technology is not only capable of analysing an array of predictive data, including a tumour’s response to therapy and the blood levels of cancer DNA during treatment, but also provides information on treatment decisions.

The tool is named as Continuous Individualized Risk Index (CIRI), and is intended to provide a single, dynamic risk assessment at any point during a treatment course.

In addition, the CIRI is capable of identifying patients who may benefit from early, more aggressive therapies, as well as those who may be potentially cured by standard methods.

Stanford University School of Medicine radiation oncology associate professor Maximilian Diehn said: “What we’re doing now is somewhat like trying to predict the outcome of a basketball game by tuning in at halftime to check the score, or by watching only the tipoff.

“We wanted to learn if it’s best to look at the latest information available about a patient, the earliest information we gathered, or whether it’s best to aggregate all of this data over many time points.”

During the study using CIRI, the team has collected data from people who were previously diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The researchers obtained information on the amount of tumour DNA circulating in the blood from 132 patients along with the initial symptoms like cancer cell type, tumour size and location from 2,500 DLBCL patients.

The data collected has been used in training the algorithm to identify patterns and combinations that could impact whether a patient lived for at least 24 months after seemingly successful therapy without a relapse.

Stanford University School of Medicine researcher Alizadeh said: “What I didn’t expect was that aggregating all this information through time may also be predictive. It might tell us ‘you’re going down the wrong path with this therapy, and this other therapy might be better. Now we have a mathematical model that might help us identify subsets of patients who are unlikely to do well with standard treatments.”